Association blog

|

Text contributed by Doug Wanstall ([email protected]) Twitter

The picture is of my grandfather, John Wanstall who witnessed the dogfight and the plane belly landing. the reaction on Twitter and facebook has been amazing and shows just how much people care about our history, heritage and the brave souls that protected us. The wreckage of the Messerschmitt Bf 109E4 (‘White 6’) piloted by Leutnant Heinz Schnabel Schnabel was captured after his Messerschmitt Bf 109E4 (‘White 6’) was shot down and crash landed in Kent on 5 September 1940 during the Battle of Britain. Schnabel was a member of Jagdgeschwader 3 (1 Staffel (squadron)) and was an ace with six confirmed 'kills' to his name at the time. "5 September 1940: 1./JG3 Messerschmitt Bf109E-4 (nr.1985). Engine damaged in combat with fighters during escort sortie for Do17s to Croydon and belly-landed on Handen Farm, Chaphill, near Aldington, 10.10 a.m. Possibly one of those attacked by F/L J.T. Webster of No.41 Squadron. FF Lt Heinz Schnabel captured slightly wounded. Aircraft White 6 + 100% write-off." Escape attempt: "Leutnant Heinz Schnabel and Oberleutnant Harry Wappler were two German prisoners of war (PoW) who made a daring, but unsuccessful attempt, to fly from captivity in England to the Netherlands during the Second World War. They managed to hijack a training aircraft and then attempt to fly to the continent, only to turn back due to lack of fuel. They were subsequently caught and later transferred to Canada for the rest of the war." - (info via wikipedia) (Colorised by Paul Kerestes from Romania)

0 Comments

Sqn Ldr Hood Sqn Ldr Hood This article originally appeared on the BBC's World War Two People's War website. The events leading to Squadron Leader HRL Hood DFC being officially listed as Missing are complex; contemporary records are now incomplete, contradictory and vague. By assembling the facts available, supplemented by eye-witness accounts and tangible relics, a clearer picture emerges which could possibly explain Squadron Leader Hoods true fate.At 1500 hrs on Thursday, 5 September 1940, Squadron Leader Hood led 12 Spitfires of 41 Squadron from Hornchurch with orders to patrol Maidstone at 15,000ft. Hood flew as Blue 1 of 'B' Flight, rearguard cover being provided by 'A' Flight, led by Flight Lieutenant Norman Ryder. The scramble was a hurried affair and, as the squadron climbed away from Hornchurch, a large enemy formation was encountered flying up the Thames Estuary towards London: He111s, Do17s and Ju88s escorted by Me109s. Other Fighter Command squadrons had been vectored to intercept this raid; the Hurricanes of North Weald's 249 Squadron, Debden's 17 and 73 Squadrons, Northolt's 303 Squadron and Stapleford's 46 Squadron. 41 Squadron Pilot Officer Wally Wallens recalls: "As usual I was flying Number 2 on 'Robin' Hood leading 'B' Flight and, being unable to gain height advantage and position in time, 'Robin' put us in line-astern and open echelon port and attacked head-on, a desperate manoeuvre that could age one very prematurely. Within seconds all hell broke loose and, as the action developed, 'B' Flight was overwhelmingly attacked by the 109s. "Only four Spitfires from 41 Squadron failed to return this engagement. Pilot Officer Tony Lovell had parachuted out of his burning aircraft over South Benfleet and returned to Hornchurch. Pilot Officer Wallens had force-landed, near Orsett, with a cannon shell through his leg and had been taken to hospital. One pilot was confirmed killed in action. His body was identified as that of Flight Lieutenant Webster DFC. Squadron Leader Hood was officially recorded as 'Missing'." Reg Lovett of 73 Squadron Another casualty of this interception and relevant to our investigation was Flight Lieutenant Reg Lovett DFC of 73 Squadron. That unit's Intelligence Report states that: "A and B flights took off from Castle Camps at 14.55 hrs with orders to orbit North of Gravesend. At 1510 approx. enemy formation sighted about 1 mile to south being engaged by A/A at 19,000ft. E/A flying westwards in 3 vics, in line astern. A Flight led by F/Lt Lovett DFC attacked the rearmost formation. Leader commenced quarter attack, but as E/A travelling very fast it developed into astern attack at 350 yards. Leader experienced considerable cross fire and was hit by MG fire on the port side. Closed to 300 yards, but hit on starboard leading edge by cannon shell, and in breaking away a Spitfire came upwards almost vertically and they collided. Leader baled out and landed near Rochford, uninjured after a delayed drop." Throughout this engagement, numerous aircraft fell to the earth below, observed by many military, police and ARP personnel, in addition to the general public. The majority of aircraft fell in the Nevendon area of Essex, adjacent to the A127, the main arterial road between London and Southend-on-Sea. The ARP telephone messages recorded: "At 15.30 approx. at Nevendon 0.25 mile SE Nevendon Hall. Machine Wrecked. Spitfire. Pilot baled out unhurt. "At 15.30 approx. Wickford. Fuselage, part body and one wing fell Cranfield Park Road 400 yards SW Tye Corner. Wing bears marking K, believed British." Further details were recorded in the War Diaries of local military units. The aircraft losses noted in the ARP records were also present in these diaries, but the following additional information was noted: "312 Searchlight Battery RA: A wing apparently belonging to a British fighter was recovered at M177010. One British pilot picked up dead on the Arterial Road at M1710. "37th AA Brigade RA: Spitfire crashed in Nevendon M180101. The pilots parachute became entangled with the plane and he was killed." An eyewitness describes the eventsJohn Watson was working at The Old Cricketers garage in Nevendon: "I could see and hear aircraft very high. Something fell into the centre of the junction and Mr Ryder, the proprietor of the shop on the corner, ran out and picked up what turned out to be a 303 bullet. As I looked up I saw an aircraft coming down. Part of the wing of this aircraft was missing and it was accompanied by a Spitfire wing. I was certain that I saw a complete Spitfire with its wing cut off, both tumbling down together. The wing came down in the direction of Wickford; the aircraft I believe may be the one which came down about 75 yards North of the present junction of Courtaulds Road and Archers Fields, on land now belonging to Essex Water and part of the treatment works. I could see a parachute coming down in the direction of North Benfleet. "As all this was going on, my attention was drawn to a Messerschmitt 109 which was also coming down in a perfect tail spin and on fire. I looked back just in time to see the British aircraft crash down nearby. As soon as I finished work, I was able to visit the crash site of the aircraft. The Hurricane had been badly damaged on hitting the ground and I was not able to get too close." For many years, various publications suggested that Terry Webster and Robin Hood had collided, but it appears more likely, given the evidence from the 73 Squadron report, that Webster actually collided with Flight Lieutenant Lovett's Hurricane. Therefore, it seems reasonable to suggest that the Hurricane which crashed a quarter of a mile South East of Nevendon Hall/Archers Fields was the aircraft vacated by the latter. This is corroborated by items recovered by Roland Wilson, on whose land the aircraft crashed. A Hurricane radio mast and Merlin II engine limitations plate were removed from the wreckage before the area was cordoned off by the authorities. The fragmentary remains of the aircraft reported on the Northern side of the arterial road were found by numerous local people. Walter Smith found the seat of the Spitfire, used by the family as a makeshift chair for many years. Roland Wilson encountered the entire tail section of the Spitfire and, daunted by the size of his souvenir, satisfied himself by removing the rudder mass balance weight and stub aerial for his collection. More importantly, some weeks later, Roland discovered an unopened parachute pack in open fields North of where he had found the Spitfire tail section. The parachute was marked 'WEBSTER'. Roland handed over the parachute to Nevendon Police, who congratulated him for his honesty. This event was recorded briefly within the Brentwood and Southend-on-Sea Police diary: "17.35 30.9.40. Nevendon. Parachute and engine of a Spitfire which crashed 5.9.40 found in a field at Nevendon." Youngsters find Spitfire wreckage a day or so after 5 September, thirteen year old Sam Armfield and his younger sister, Brenda, were on their way through scrubland, known locally as 'The Police Bushes' on account of being opposite the A127 Police Houses. The youngsters were en-route to fish at a pond. In the wasteland they were astonished to encounter the virtually intact wreckage of a Spitfire which was lying on the surface and hidden by the tall bushes. The entire fuselage forward of the control panel was missing, but there was no other indication of battle damage. Sam recalls: "The Spitfire obviously couldn't be seen from the main road, otherwise soldiers or Home Guard would have been guarding the aircraft. I don't recall any signs of bullet or cannon holes and no blood or anything in the cockpit - we would have looked for that sort of thing. The tail wheel was clear of the ground and we all commented on what a good wheelbarrow wheel it would make. None of us could remove it. We all took turns to climb in the cockpit and pretend to fly it, but we were all reluctant to press the gun firing button on the control column. We were able to remove the gun inspection covers and discovered that all the ammunition had been exhausted and the webbing belts were slightly frayed from passing through the guns." Brenda Armfield recalls that she discovered the severed port wing on the other side of the bushes, some eight feet away from the main wreckage. The wing had separated at the last inboard gun position and the Browning machine gun was exposed. Brenda used the small screwdriver from her sewing kit to take off the ammunition feed chute, which was already loose. The boys were jealous of her prize and made unsuccessful attempts to remove the gun itself. Every evening after school the youngsters would rush home to play on the aircraft and make further attempts to remove various souvenirs. Although they told no adults about 'their' Spitfire, after about a week they arrived to find that the wreck had been removed. The engine of this aircraft appears to have fallen further West of the main crash location, near Great Wasketts Farm. Apparently, the Merlin was shattered and many fragments lay scattered about the impact spot. The engine was guarded by a member of the LDV, although Sam Armfield managed to obtain some souvenirs which have since been identified as being of Rolls-Royce Merlin origin. Although the eye-witnesses have identified this aircraft as a Spitfire, the lack of battle damage confirms the fact that it could not have been Lovett's Hurricane, which had been badly damaged by the enemy - 73 Squadron Intelligence Report refers. Only one Spitfire remains unaccounted for: Squadron Leader Hood's P9428 EB - R. This may well have been his aircraft. It is quite possible that the Spitfire discovered by Sam Armfield was that referred to in the War Diary of the 37th AA Brigade RA, although it is unclear why the wreckage was not discovered by the authorities earlier. The report states that the pilot's parachute became entangled with the plane prior to his death. However, there appears to be no firm evidence to confirm the recovery of the body of the pilot from this particular aircraft, or its subsequent burial. It is understood from the Pitsea undertaker, Mr Green (who was responsible that day for the recovery of a German Casualty, Hauptmann Fritz Ultsch) that the bodies of all airmen were initially taken to local mortuaries before being collected en-masse by Frank Rivett and Sons of Hornchurch. The bodies were then transferred to RAF Hornchurch for distribution and burial. The records of Frank Rivett and Sons were apparently destroyed during the Blitz. The Luftwaffe cemetery The absence of any records relating to local undertakers makes positive identification of the final resting place of this pilot difficult to establish. Allied airmen were generally buried in the graveyard at St Andrews Church, Hornchurch, unless it was requested otherwise by the family of the deceased. Luftwaffe casualties were interred at Becontree Cemetery and it is here that an interesting anomaly has been noted. Within the Barking and Dagenham Burial Register, Entry No. 5176 records the burial of a Walter Heatz/Heatry (Register no. 5/09/11) on 12 September 1940 in grave B1:684 - the day after the burial of Hauptmann Fritz Ultsch. The GWGC have confirmed that they have no record of any relevant casualty and, consequently, the body has never been transferred to Cannock Chase. Interestingly, the original entry 5176 in the Burial Register has been altered at some time in the past and the name of Walter Heatz has been crossed out and the name Walter Klotz added in pencil. The name Walter Heatz then reappears lower down in the register under Entry No. 5206, on 26 October 1940, where the name unknown has been crossed out and W. Heatz added, also being buried in Grave B1:684. Given that some major errors were obviously made at this time, further research is currently being undertaken to examine the possibility that this grave may actually be the final resting place of Squadron Leader Hilary Richard Lionel 'Robin' Hood DFC. In conclusion, it is believed that whilst attacking the bombers head-on, B Flight of 41 Squadron were bounced by JG54. The exact cause of Squadron Leader Hood's loss remains unconfirmed, although there is one combat claim by Timmerman of 1/JG54 which may possibly relate to this casualty. Hood appears to have baled out, but his parachute became entangled with his aircraft with fatal consequences. Spitfire P9428 then tumbled down, engine-less and minus its port wing, landing near the arterial road in Nevendon. Whatever injuries Squadron Leader Hood sustained whilst baling out will never be know, but it must be presumed that they were such that personal identification was not possible. As it has recently been accepted that Flight Lieutenant Rushmer lies in the 'unknown' grave at Staplehurst, there are no other unidentified RAF casualties with this date of death. Could it be, therefore, that at some point between collection of the body and its eventual burial, a mistake has been made leading to Hood's burial as a non-existent German airman? I doubt we will ever know, but from the evidence available, and fantastic as this theory sounds, it has to be considered a very distinct possibility. The following pictures and war record were provided by Peter Lee about his cousin, Flight Sergeant Teddy Watts. WATTS, Edward George Hullet ‘Teddy’, 1051882, RAFVR;

b London, 11 Feb 19; ed Holborn GS; joined RAFVR, 29 Jul 40; 9 EFTS, Ansty, 1940; Crse 28, 9 SFTS (Master & Hurr), Hullavington, 1940-16 Apr 41; plt badge & Sgt Plt, 16 Apr 41; Crse 20, 57 OTU (Spit), Hwdn, 23 Apr-9 Jun 41; RF/WUL in Spit Ia, K9942, Hwdn, 16 May 41; 501 Sqn (Spit II), Chilbolton, 19 Jun 41; 145 Sqn (Spit II), Merston, 10 Jul 41; 485 (NZ) Sqn (Spit Vb), Redhill, 1 Sep 41; 41 Sqn, 3 Dec 41-12 Apr 42; 7 days leave, 22 Dec 41; 7 days leave, 22 Jan 42; Flt Sgt, ca Apr 42; SD/KIA in Spit Vb, W3450, in combat w FW190s during Circus 122 to Hazebrouck Marshalling Yards, 12 Apr 42, aged 22; s of Edward A. & Beatrice Watts, & husb of Margaret Watts of Stockwell, London; bur Plot 2, Row 3, Grave 5, Dunkirk Town Cem Nord, F. The full extent of the activities conducted by 41(R) TES cannot be shared online, however you can get a sense of the scope and complexity involved in this recent publication by David Gledhill and David Lewis. The Squadron hold very little information covering the years that it operated the Bloodhound Missile (1965-1970). Fortunately the Bloodhound Missile Preservation Group (BMPG) have an excellent resource of information on their website and YouTube channel. Read more below: The Bloodhound MKII missile system, as operated by 41 Squadron, was a key part of the integrated UK air defences during the Cold War, a wholly British designed defensive weapon to counter nuclear armed, high flying bombers at long range. Bloodhound MKII became operational with the RAF in 1964 and continued to be improved as new technology became available with its operational role continually enhanced to include the countering of low level air strikes. The missile system was withdrawn from RAF service in 1991, at the end of the Cold War. You can learn more about how the system worked through the following reports

Originally posted on the website of the Bentley Priory Museum To mark his 95th birthday, Warrant Officer (Retd.) Peter Hale RAF has taken to the air in a Spitfire again – the first time he has done so since 1945. On this occasion, he was a passenger in the Goodwood-based two-seater SM520. Arranged by author and Westhampnett historian Mark Hillier, the flight was provided courtesy of his colleagues at the Boultbee Flying Academy. The Academy offers flights and experiences around the UK in an ever-expanding fleet of owned and managed Second World War aircraft, including SM250. Completed in the Castle Bromwich factory on 23 November 1944, SM250, initially built as a single seat Mark H.F.IXe high level fighter, was delivered to No.33 Maintenance Unit at Lyneham in Wiltshire where it was to be prepared to operational standard for service delivery. Fitted with a Rolls-Royce Merlin 70 V12 engine, SM 250 was sold to the South African Air Force on 21 June 1948. One of a batch of 136 Spitfires earmarked for delivery to South Africa between 1947 and 1949, it is known that SM250 was off-loaded at Durban in 1948. Eventually sold as surplus, SM250 was registered in the UK in 1997, following which the decision was taken to convert her into a Trainer 9 two-seater. With Jez Attridge, the former Officer Commanding RAF Coningsby at the controls of SM250, the flight was an emotional experience for Peter – stirring memories of his time flying Spitfires with 41 Squadron between August 1944 and August 1945. One sortie that he recalled was a 125-Wing operation from Celle, Germany, on 24 April 1945. Peter recalled how on this day the Wing, led by Group Captain Johnnie Johnson, headed east towards Berlin following reports of a large concentration of airborne German aircraft. It was discovered, however, that they were in fact Russian ’planes attacking retreating German troops around twenty-five miles WNW of Berlin. Peter, then a 22-year-old NCO pilot, noted how the Red Air Force fighters ‘were all over the sky with no obvious formation. They suddenly appeared in the sky like a swarm of bees.’ The RAF pilots, however, proceeded to join the Russians in their ground attacks, this being one of the few instances of contact between RAF and Russian fighters during the war. Having joined the RAF in January 1941, Peter undertook his elementary flying training in the UK before being shipped to Canada to undertake his service flying training. However, rather than being sent home for operational duties after receiving his Wings in April 1942, he was retained in Canada for a further eighteen months as a staff pilot and instructor. Finally released in October 1943, he returned home from New York on the majestic troopship Queen Mary. After advanced flying and operational training, he was posted to 41 Squadron on 8 August 1944, by which time he had been promoted to Warrant Officer. From this point on Peter was in the thick of the action, commencing with patrols over south-east England to combat the flying bomb threat. These sorties were closely followed by others that were part of the hunt for V2 and V3 sites, escorts to USAAF bombers involved in the Oil Campaign, and air support for Operation Market Garden.

In December 1944, 41 Squadron moved to the Continent. It spent the ensuing months venturing deeper into Germany, mainly deployed on attacking ground targets behind the front. Its Spitfires were also regularly involved in brief but aggressive aerial combats. When, in mid-April 1945, 41 Squadron moved to Celle Aerodrome, approximately 140 miles west of Berlin, it became one of the first Allied air units to be based east of the Weser. Following the German surrender, Peter remained with 41 Squadron until August 1945, when he was posted out to India. Returning home in time for Christmas 1945, he was demobilised in June 1946. Peter spent the next thirty-five years with the Met Office, but did not fly a Spitfire again until the flight in SM520. This blog entry has been made possible by Mike Bradbury. Over the last few months in and around Shrewsbury there have been two functions with Eric as a big part in his memory. The first one held on March the 3rd at Bayston Hill, the village of his birth, when a stained glass window was unveiled in his memory by Flight Lieutenant Laura Frowen 41 Squadron, Wing Commander Steve Chaskin OC 611 Squadron and Rosemarie Jones, Eric's niece. On the 24th of June Shrewsbury held it's Armed Forces Day, at 23 30 on the 23rd running up to this a light show was put on, this covered pictures starting back as far as the Boer War up to present day of people from Shropshire who served in the armed forces. These images were projected onto St Chads Church and a large part of this show was devoted to Eric, and for just this part I did the voice over telling just a short part of his service with 41 and 611 Squadron's and his life story.

This article was originally posted on the RAF Website. RAF Coningsby Gate Guardian, Phantom FGR2, XT891

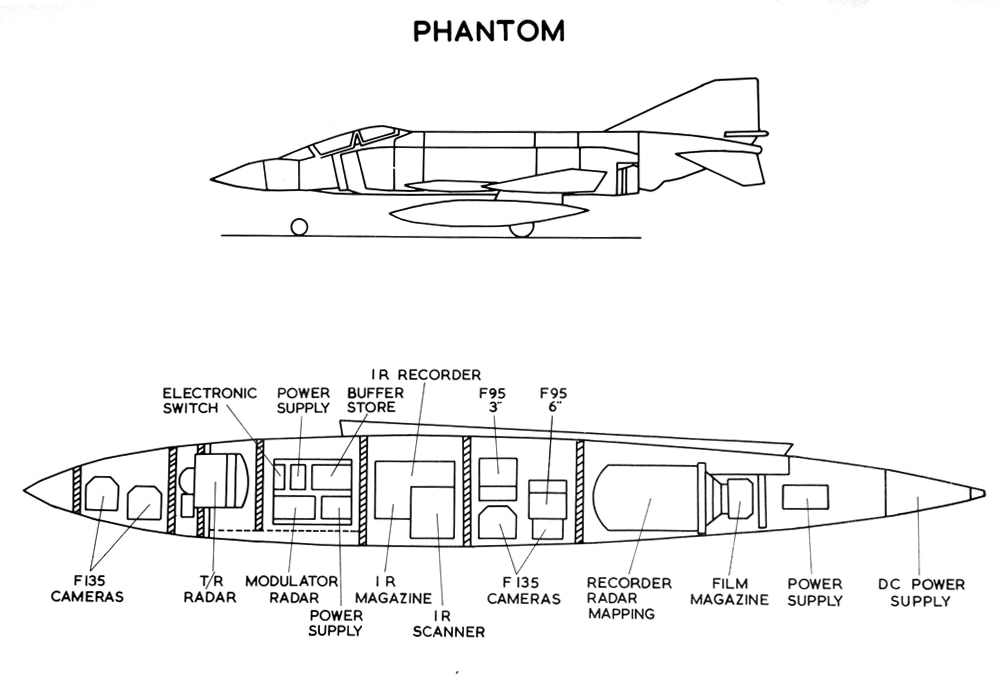

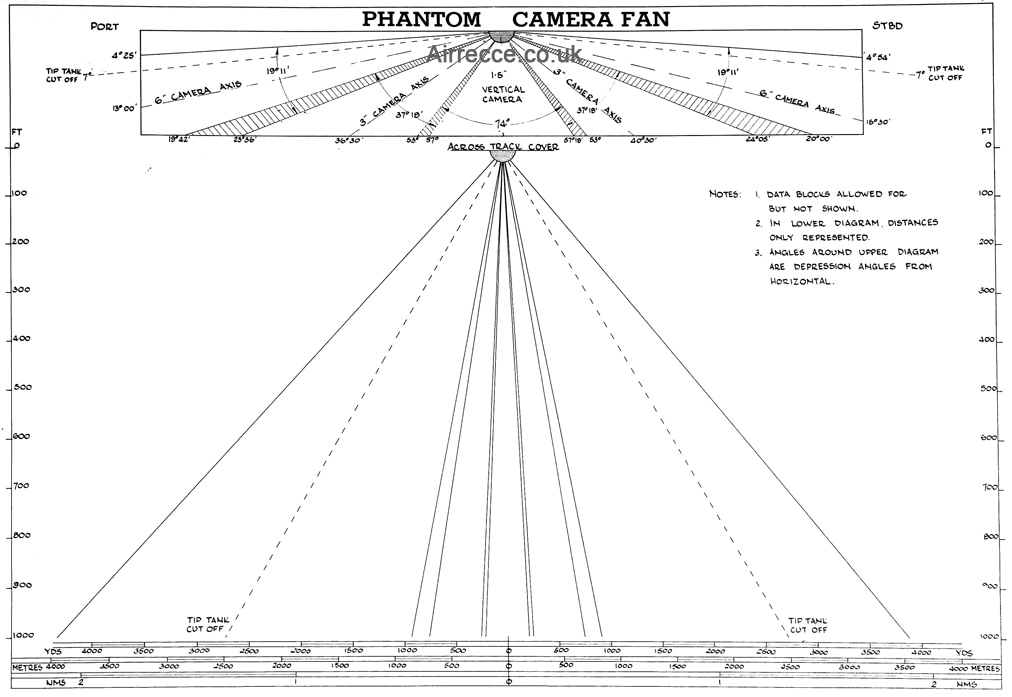

Some aircraft hold a special place in RAF history and XT891, the RAF Coningsby Gate Guardian is certainly one. It was not the first Phantom delivered to the UK as that accolade goes to a prototype YF-4K which first flew on 27 June 1966 at the McDonnell Douglas plant in St. Louis. XT891, however, was the first delivered for operational service to the Royal Air Force. Group Captain Stanley Mason formally accepted XT891, an F4M designated the FGR2 (Fighter, Ground Attack, Reconnaissance) in RAF service, in a ceremony at RAF Aldergrove on 20th July 1968. After acceptance, it arrived on 228 Operational Conversion Unit, or OCU, on 23 August 1968. A twin stick variant, the rear cockpit had a different configuration to the normal Phantom. The layout of the cockpit consoles was revised to accommodate the throttles which were mounted on the left. Although these operated normally in the military power range, reheat could not be selected in the back. An enhanced flight instrument cluster sat at eye level in the back seat, although it restricted the forward view considerably. The floor mounted control column allowed the flying instructor in the rear cockpit to take control when needed. The “stick” could be removed to allow the radar scope to be pulled out from its housing, otherwise impossible if a stick was installed. For intercept training sorties this was the preferred configuration, although occasionally it remained fitted, allowing the staff navigators some “stick time”. The trainer configuration was less common and each operational squadron had only one twin sticker although a much higher proportion were operated by the OCU at Coningsby because of the increased training task as pilots converted to the Phantom. In all other respects it was fully capable operationally. Soon after its arrival XT891 moved across to 54 Squadron in the ground attack role remaining at Coningsby for some years serving another short stint on the OCU. When 56 Squadron reformed with Phantoms it became the Squadron “two sticker” serving as “Zulu” at RAF Wattisham before returning to the OCU at Coningsby and, eventually moving to RAF Leuchars where it wore the tail letters “Charlie Zulu”. Another stint at RAF Wattisham as “Sierra” on 74 Squadron ended its service career and it returned to its spiritual home at RAF Coningsby. Once retired, officially, it adopted a ground instructional airframe number, 9136M, although it continues to wear its operational registration marks. Soon after being placed on display as the Station Gate Guardian it was repainted in the colours in which it first served in 1968. The square fin cap for the radar warning receiver was removed to return it to its original configuration and it reverted to the grey and green camouflaged pattern with red, white and blue roundels reminiscent of its early service during the Cold War. In subsequent years both 6 Squadron and 41 Squadron, both of which operated the type but not the actual airframe, laid claim to the airframe adding their own squadron markings. The following information has been collated from: www.spyflight.co.uk/ and www.airrecce.co.uk/ together with assistance from Ray Dunn. In 1964 the Labour government of Harold Wilson cancelled the P1154 and TSR-2 programmes, leaving the RAF without obvious replacements for the Hunter and Canberra in the fighter, ground attack and reconnaissance roles. The RAF eventually decided to follow the Royal Navy's decision to purchase the McDonnell Douglas F-4 and in Feb 65 placed an order for 118 F-4's to take over the roles of the Hunter and Canberra. In RAF service the Phantom was known as the FGR2, with the initials standing for Fighter, Ground Attack and Reconnaissance. Unlike the USAF and US Marines, the RAF did not obtain Phantoms that was solely for photographic reconnaissance, the RF-4 series. The F-4 OCU at Coningsby was formed in Aug 1968 and the initial output of graduates formed the ground attack squadrons in Germany and UK. The first dedicated F-4 reconnaissance squadron to form was 2 Sqn based at Laarbruch in Germany which stood up in Dec 70. This was followed by 41 Sqn at Coningsby which formed in Apr 72. Only some thirty F-4's were specially wired to carry the EMI reconnaissance pod and these aircraft equipped 2 and 41 squadrons. The pod was pressurised and mounted on the aircrafts centre-line position, looking like a 500 gal external fuel tank, it had a fat bottom and an air scoop on each side of the pods forward nose section. Using a considerable amount of technology originally developed for the TSR2 reconnaissance systems, EMI eventually created the biggest, most capable and most expensive reconnaissance pod of the 1960s.  Starting at the front the pod was fitted with the following equipment, two AGI F.135 cameras, a Texas Instrument RS700 infar-red linescan (ILRS) sensor, four F.95 cameras in the oblique position, these could replaced with another split pair of F.135 cameras for night tasking. All of the F-135's were vertical facing. When in the 'Night-Flashing' mode, four F-135's were used, three of them were arranged in a split-pair 'fan', the fourth camera was used as a timer unit to synchronise with the electronic flash unit in the port Sargent Fletcher tank. Along each side of the pod were the 15 ft slotted waveguide aerials for the MEL/EMI Q-band Sideways Looking Reconnaissance Radar (SLRR). This scope of reconnaissance equipment fitted gave a horizon-to-horizon coverage, however, there was a loss of 4½° on each horizon due to the external fuel tanks mounted under the aircrafts wings. For special tasks, a F126 vertical camera and an F95 oblique camera with a 12in focal lens could also be fitted. The only 'forward-facing' camera used was an F-95 in the 'Strike-pod' which was fitted to the port forward sparrow position. It had a depression angle of 20° from the horizontal.  The exposure rate of each camera could be selected to run at 4, 6, 8, or 12 frames per second, though normal settings were either 8 or 12 depending on what height the aircraft was flying. The IRLS could cover an area of three times the aircrafts height. When using the SLLR the aircraft had to fly straight and level as the system was not roll stabilised. The system could cover an area of five miles when the aircraft was operating at normal low-level height, this increased to ten miles when flying at 6,000ft, however, there was a degradation of image quality. The Jaguar used a new build EMI recce pod when it took over the role of tactical reconnaissance from the FGR2 in 1976. The Jaguar pod featured a different mark of F-95 camera (Mark 10), and used a different IRLS, 70mm rather than the 5'' format used on the Phantom EMI Pod. |

Photo Credit:

Rich Cooper/COAP Association BlogUpdates and news direct from the Committee Archives

August 2022

Categories

All

|

||||||||||