Association blog

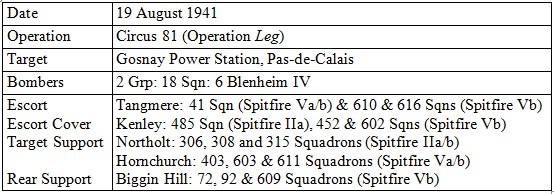

When baling out of his stricken aircraft on 9 August 1941, Wg Cdr Douglas Bader was compelled to leave behind his right artificial leg as it was stuck in the cockpit. He unstrapped the prosthesis and jumped with only his left artificial leg, and was injured on landing, damaging the ‘good’ leg, and breaking the waist harness in the process; the leg that had remained... with the aircraft was destroyed when his Spitfire hit the ground. Bader was hospitalised for a short period in St. Omer, from where he managed to escape with the help of a French nurse, but had barely reached the home of a local farmer when he was found and re-captured. In much the same way that Galland, Mölders, and other German Aces were respected by the Allies, and indeed pilots before them such as von Richthofen and Udet, so too was Bader by the Luftwaffe. Being in a rather uncomfortable position without the full use of his legs, he therefore used his status to ask them if they might arrange for the RAF to drop a replacement right leg. In a rare case of collaboration between two countries at War, the Luftwaffe assented to Bader’s request and sent a message to the RAF to arrange it. Thus, Operation Leg was born, and formed a part of Circus 81 on the morning of 19 August. Officially, the aim of the mission was to attack Gosnay Power Station, which, ironically perhaps, was the failed target of Circus 68 on 9 August – the very operation Bader was lost on. However, the secondary, although preliminary, objective was to drop Bader’s leg by parachute. The Luftwaffe offered the RAF a safe thoroughfare to St. Omer but once the job was done the ‘ceasefire’ was over and the war was back on; the bombers and fighters would continue on to their attack on Gosnay. The Operation Order for Operation Leg foresaw the bombers making rendezvous over Manston at 10,000 feet at 08:30, with Tangmere’s Escort Wing stepped up and back at 11,000, 12,000, and 14,000 feet, the Escort Cover Wing at 15,000, 17,000 and 20,000, the Target Support Wings at 22,000, 24,000, 28,000, and 32,000 feet, and finally the Rear Support Wing at 28,000 and 32,000 feet. The orders pertaining to the dropping Bader’s leg also included a role for the Tangmere Wing: “The leg is to be dropped by a Blenheim when West of ST. OMER. The Wing Leader of the Tangmere Escort Wing is to report by R/T when the parachute has opened ‘LEG GONE’. Tangmere Controller is to report to Group Controller immediately he receives this message.” In the event, the Circus was delayed by two hours and the Tangmere Wing was airborne at 10:05, and rendezvoused with the Blenheims over Manston at 10:30. 41 Squadron deployed eleven pilots led by Sqn Ldr Gaunce and provided a Close Escort for the bombers at 11,000 feet. 41 Squadron comprised Gaunce P8759, Beardsley W3565, Rayner W3636, Mitchell W3383, Morgan R7350, Glen R7307, Marples W3713, Palmer W3564, Swanwick W3634, Bodkin R7304, and, Brew R7267. Kenley’s Escort Cover Wing also rendezvoused over Manston with the bombers and Tangmere Wing, and they proceeded together uneventfully to St. Omer via Dunkirk. At 10:57, 18 Squadron Blenheim IV, R3843, dropped Wg Cdr Bader’s replacement right artificial leg over the southwest corner of St. Omer Airfield from 10,000 feet; the parachute opened and Wg Cdr Woodhouse confirmed this fact to the Tangmere Controller. The specially built wooden crate that was dropped was clearly marked with a large Red Cross symbol, and landed near the village of Quiestède. The formation then continued on to Gosnay, approximately three-and-a-half miles southwest of Béthune, to complete the main objective of the Circus. Intent on making a bombing run at 10,000 feet, the bomber crews were once again foiled when they found ten-tenths cloud cover over the target area. This was mostly concentrated between 8,000 and 10,000 feet, but large cumulus clouds reached up to 20,000 feet, and storm clouds were scattered over the target area. This left them little choice but to abandon the attack, and Gosnay was spared yet again. No alternative target was located and no bombs were dropped at all. The Tangmere Wing did not sight the Luftwaffe all the way to the target, and turned with the bombers to escort them back out. The Blenheims’ return was initially covered by the same cloud cover that had thwarted their attack, but the weather deteriorated as they neared the coast and the bombers were forced to drop to just 1,000 feet to get under the cloud base. This resulted in them being fired at by the German coastal defences, which were no doubt surprised to see six RAF bombers roar over their heads at little more than 300 metres. The result was that all the aircraft were hit by Flak and one man was wounded. The Tangmere Wing sighted a few German aircraft on their way out but they showed no inclination to fight and were not engaged. The three squadrons left the bombers about ten miles off Manston and made for Westhampnett and Merston, where they landed in time for lunch at 12:00. The Kenley Wing, on the other hand, saw and engaged a number of Luftwaffe aircraft. 452 Squadron was attacked from behind approximately 15 miles inland and one aircraft was hit by cannon and forced to return home early. On the way back out, the Squadron was continuously attacked by Me109s, which split the pilots up, and cost the lives of Fg Off Eccleton and Sgt Plt Gazzard, whilst Plt Off Willis was wounded in action. In return, they claimed one Me109F destroyed and two probably destroyed. A section from 602 Squadron dived to attack three enemy aircraft below them without result, and another section was dived upon by three Me109s from above, but neither a claim nor a casualty was subsequently reported. On the way back out again, a number of small formations of Me109s also attacked 485 Squadron and several engagements took place, resulting in the loss of Sgt Plt Miller, for claims of one Me109 destroyed, one probably destroyed and one damaged. Northolt’s Target Support Wing made landfall on the French coast west of Gravelines at 10:45, stepped up and back at 22,000, 25,000 and 27,000 feet. Approximately five minutes after crossing in, they were attacked by 15 Me109s in two formations. 306 Squadron went into a defensive circle and subsequently claimed an Me109F destroyed for no loss, whilst 308 Squadron split up and claimed another destroyed, but lost the rest of the Wing in the process and patrolled the coast for ten minutes before returning home. 315 Squadron had difficulty maintaining contact with 306 and 308 Squadrons on account of cloud and were not engaged at all. However, pilots of the Wing report seeing an Me109 hit and destroyed by German Flak in the Calais area. Hornchurch’s Target Support Wing crossed the French coast six miles east of Dunkirk between 28,000 and 32,000 feet at 10:45. 611 Squadron sighted ten Me109s 24,000 feet over Poperinghe, Belgium, which they chased all the way to Dunkirk without result. 403 Squadron attacked another 15 Me109s in the Poperinghe area and ultimately claimed four destroyed, one probably destroyed and two damaged for the loss of Plt Off Anthony, who was shot down and captured, and Plt Off Dick who baled out off Dover with combat damage and was rescued by ASR. Soon after crossing in, 603 Squadron sighted 20 Me109s approaching from the south at 20,000 feet. They were engaged by one of the Squadron’s sections, which claimed two destroyed, two probably destroyed and one damaged for no loss, whilst the rest of the unit covered them at 30,000 feet. Ultimately, none of the Wing’s squadrons reached the Gosnay area, and they withdrew after they had been informed that the bombers had crossed out. Finally, Biggin Hill’s Rear Support Wing, made landfall on the French coast ten miles southeast of Dunkirk, between 27,000 and 28,000 feet. The Wing then made a wide sweep to starboard and in doing so sighted a number of formations of two to four Me109s at altitudes down to 13,000 feet. Whilst 72 and 92 Squadrons remained above for cover, 609 Squadron dived down to attack the enemy aircraft, and claimed two damaged. The Squadron’s Plt Off Ortmans sustained combat damage and baled out into the Channel but was picked up by ASR and returned safely. [Excerpts from my “Blood, Sweat and Courage” (Fonthill, 2014). Sharing permitted, but no reproduction without prior permission, please]

1 Comment

Supermarine "Spitfire" Mk.I coded serial number N3126 EB-L of 41 Squadron of the Observer Corps, flown by Pilot Officer Ted "Shippy" Shipman, then based at RAF Catterick. On 15 August 1940 he shot down the Messerschmitt Bf-110C Zerstörer coded M8 + CH of Staffel 1 Zerstörergeschwader 76 -1./ZG76- piloted by Oblt. Hans Ulrich Kettling. The combat was filmed by the movie machine guns "Spitfire". The 3rd photo depicts what remains of Oblt. Hans Ulrich Kettling's Messerschmitt Bf-110C after the crash. The last picture shows Ted Shipman (left) and Hans Ulrich Kettling well after WW2, when they met in 1985.

Extract from One Of 'The Few". The Memoirs of Wing Commander TED 'SHIPPY' SHIPMAN AFC by John Shipman. To mark his 95th birthday, Warrant Officer (Retd.) Peter Hale RAF has taken to the air in a Spitfire again – the first time he has done so since 1945. On this occasion, he was a passenger in the Goodwood-based two-seater SM520. Arranged by author and Westhampnett historian Mark Hillier, the flight was provided courtesy of his colleagues at the Boultbee Flying Academy. The Academy offers flights and experiences around the UK in an ever-expanding fleet of owned and managed Second World War aircraft, including SM250. Completed in the Castle Bromwich factory on 23 November 1944, SM250, initially built as a single seat Mark H.F.IXe high level fighter, was delivered to No.33 Maintenance Unit at Lyneham in Wiltshire where it was to be prepared to operational standard for service delivery. Fitted with a Rolls-Royce Merlin 70 V12 engine, SM 250 was sold to the South African Air Force on 21 June 1948. One of a batch of 136 Spitfires earmarked for delivery to South Africa between 1947 and 1949, it is known that SM250 was off-loaded at Durban in 1948. Eventually sold as surplus, SM250 was registered in the UK in 1997, following which the decision was taken to convert her into a Trainer 9 two-seater. With Jez Attridge, the former Officer Commanding RAF Coningsby at the controls of SM250, the flight was an emotional experience for Peter – stirring memories of his time flying Spitfires with 41 Squadron between August 1944 and August 1945. One sortie that he recalled was a 125-Wing operation from Celle, Germany, on 24 April 1945. Peter recalled how on this day the Wing, led by Group Captain Johnnie Johnson, headed east towards Berlin following reports of a large concentration of airborne German aircraft. It was discovered, however, that they were in fact Russian ’planes attacking retreating German troops around twenty-five miles WNW of Berlin. Peter, then a 22-year-old NCO pilot, noted how the Red Air Force fighters ‘were all over the sky with no obvious formation. They suddenly appeared in the sky like a swarm of bees.’ The RAF pilots, however, proceeded to join the Russians in their ground attacks, this being one of the few instances of contact between RAF and Russian fighters during the war. Having joined the RAF in January 1941, Peter undertook his elementary flying training in the UK before being shipped to Canada to undertake his service flying training. However, rather than being sent home for operational duties after receiving his Wings in April 1942, he was retained in Canada for a further eighteen months as a staff pilot and instructor. Finally released in October 1943, he returned home from New York on the majestic troopship Queen Mary. After advanced flying and operational training, he was posted to 41 Squadron on 8 August 1944, by which time he had been promoted to Warrant Officer. From this point on Peter was in the thick of the action, commencing with patrols over south-east England to combat the flying bomb threat. These sorties were closely followed by others that were part of the hunt for V2 and V3 sites, escorts to USAAF bombers involved in the Oil Campaign, and air support for Operation Market Garden.

In December 1944, 41 Squadron moved to the Continent. It spent the ensuing months venturing deeper into Germany, mainly deployed on attacking ground targets behind the front. Its Spitfires were also regularly involved in brief but aggressive aerial combats. When, in mid-April 1945, 41 Squadron moved to Celle Aerodrome, approximately 140 miles west of Berlin, it became one of the first Allied air units to be based east of the Weser. Following the German surrender, Peter remained with 41 Squadron until August 1945, when he was posted out to India. Returning home in time for Christmas 1945, he was demobilised in June 1946. Peter spent the next thirty-five years with the Met Office, but did not fly a Spitfire again until the flight in SM520. |

Photo Credit:

Rich Cooper/COAP Association BlogUpdates and news direct from the Committee Archives

August 2022

Categories

All

|