Association blog

|

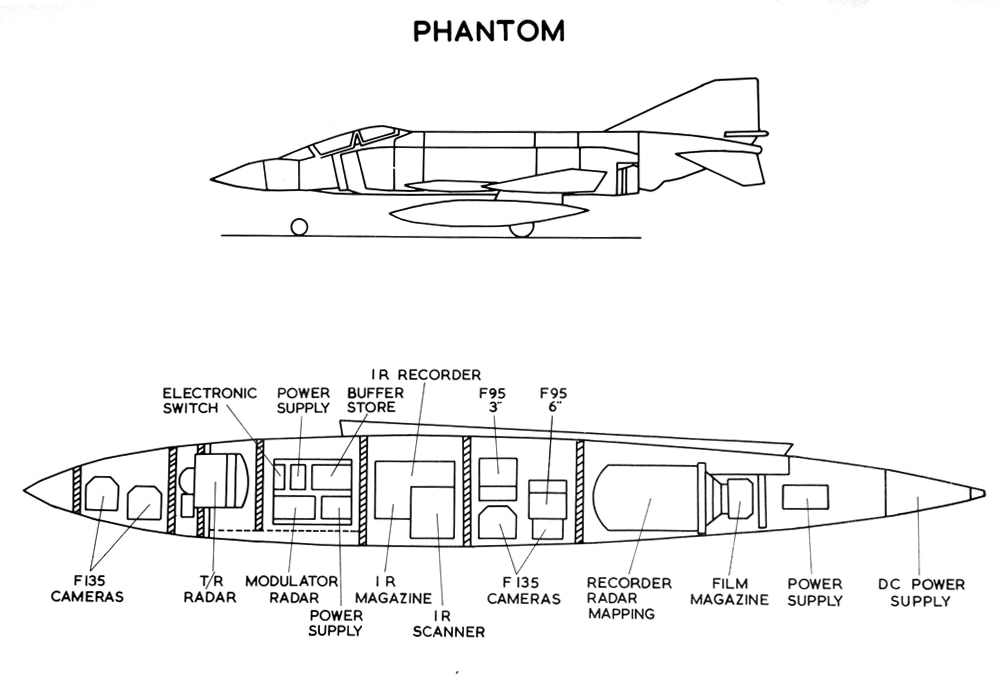

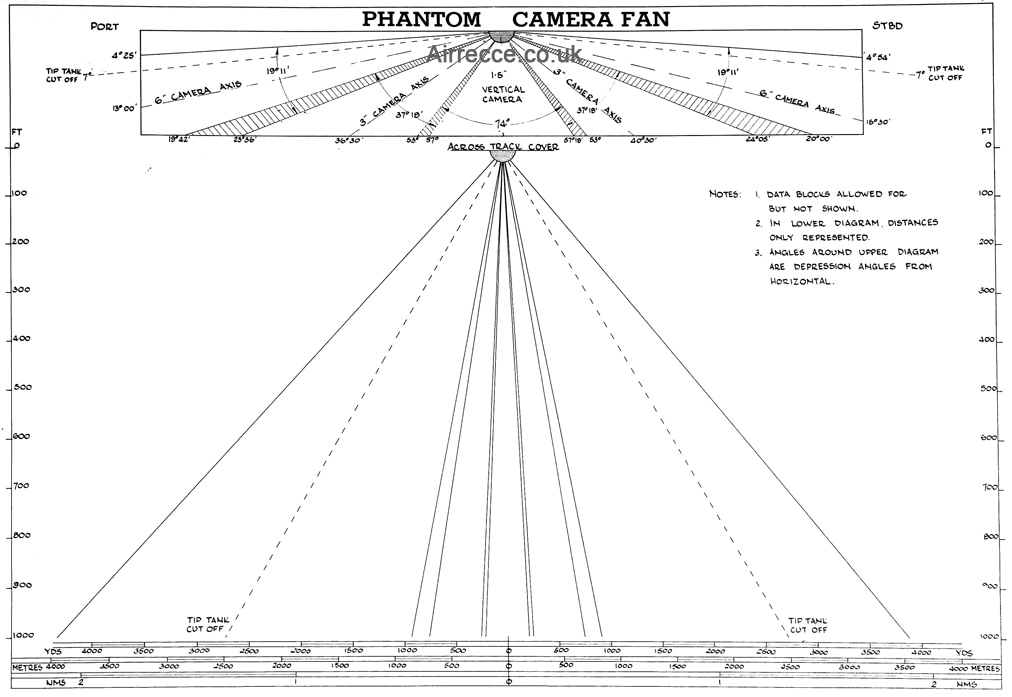

The following information has been collated from: www.spyflight.co.uk/ and www.airrecce.co.uk/ together with assistance from Ray Dunn. In 1964 the Labour government of Harold Wilson cancelled the P1154 and TSR-2 programmes, leaving the RAF without obvious replacements for the Hunter and Canberra in the fighter, ground attack and reconnaissance roles. The RAF eventually decided to follow the Royal Navy's decision to purchase the McDonnell Douglas F-4 and in Feb 65 placed an order for 118 F-4's to take over the roles of the Hunter and Canberra. In RAF service the Phantom was known as the FGR2, with the initials standing for Fighter, Ground Attack and Reconnaissance. Unlike the USAF and US Marines, the RAF did not obtain Phantoms that was solely for photographic reconnaissance, the RF-4 series. The F-4 OCU at Coningsby was formed in Aug 1968 and the initial output of graduates formed the ground attack squadrons in Germany and UK. The first dedicated F-4 reconnaissance squadron to form was 2 Sqn based at Laarbruch in Germany which stood up in Dec 70. This was followed by 41 Sqn at Coningsby which formed in Apr 72. Only some thirty F-4's were specially wired to carry the EMI reconnaissance pod and these aircraft equipped 2 and 41 squadrons. The pod was pressurised and mounted on the aircrafts centre-line position, looking like a 500 gal external fuel tank, it had a fat bottom and an air scoop on each side of the pods forward nose section. Using a considerable amount of technology originally developed for the TSR2 reconnaissance systems, EMI eventually created the biggest, most capable and most expensive reconnaissance pod of the 1960s.  Starting at the front the pod was fitted with the following equipment, two AGI F.135 cameras, a Texas Instrument RS700 infar-red linescan (ILRS) sensor, four F.95 cameras in the oblique position, these could replaced with another split pair of F.135 cameras for night tasking. All of the F-135's were vertical facing. When in the 'Night-Flashing' mode, four F-135's were used, three of them were arranged in a split-pair 'fan', the fourth camera was used as a timer unit to synchronise with the electronic flash unit in the port Sargent Fletcher tank. Along each side of the pod were the 15 ft slotted waveguide aerials for the MEL/EMI Q-band Sideways Looking Reconnaissance Radar (SLRR). This scope of reconnaissance equipment fitted gave a horizon-to-horizon coverage, however, there was a loss of 4½° on each horizon due to the external fuel tanks mounted under the aircrafts wings. For special tasks, a F126 vertical camera and an F95 oblique camera with a 12in focal lens could also be fitted. The only 'forward-facing' camera used was an F-95 in the 'Strike-pod' which was fitted to the port forward sparrow position. It had a depression angle of 20° from the horizontal.  The exposure rate of each camera could be selected to run at 4, 6, 8, or 12 frames per second, though normal settings were either 8 or 12 depending on what height the aircraft was flying. The IRLS could cover an area of three times the aircrafts height. When using the SLLR the aircraft had to fly straight and level as the system was not roll stabilised. The system could cover an area of five miles when the aircraft was operating at normal low-level height, this increased to ten miles when flying at 6,000ft, however, there was a degradation of image quality. The Jaguar used a new build EMI recce pod when it took over the role of tactical reconnaissance from the FGR2 in 1976. The Jaguar pod featured a different mark of F-95 camera (Mark 10), and used a different IRLS, 70mm rather than the 5'' format used on the Phantom EMI Pod.

8 Comments

The USSR's Military Intervention in the Egyptian-Israeli Conflict Isabella Ginor and Gideon Remez Gideon Remez writes: Reading about 41 Squadron's operation of F-4 Phantoms, I thought Association members might be interested in this new book that I co-authored with my "better half," Isabella Ginor. One of the book's main themes is the head-on clash between Israel's newly acquired F-4s and Soviet-manned SAMs -- see the attached painting from the museum of Russia's Air Defense Corps. This duel largely determined the outcome of the Egyptian-Israeli War of Attrition (1969-70) and Yom Kippur War (1973). The book also quotes several dispatches that my father, former 41 Sqn pilot Aharon Remez, sent from his post as Israel's ambassador the the UK, 1965-1970. Isabella and I will be presenting the book at Oxford University's Centre for Hebrew and Jewish Studies on 18 May and at the South Hampstead Synagogue, London, on 22 May -- see the hyperlinks for details. We'd be delighted to welcome 41 Sqn veterans! In the May issue of AirForces Monthly we take a look at the varied work of No 41 (Reserve) Test and Evaluation Squadron at RAF Coningsby. AFM spoke to members of the unit that is responsible for ensuring the Royal Air Force gets the very best out of its Tornados and Typhoons.

In broad terms, No 41(R) TES tests and assesses fast jet systems and upgrades that are bound for the operational units. The drawdown in different fighter types flown by the RAF is reflected in the 41(R) TES inventory – today it fields just three Tornado GR4s and six Eurofighter Typhoons. Its sister squadron No 17(R) TES is responsible for the F-35B under a similar mandate across at Edwards Air Force Base, California. Although its days in service are numbered, the Tornado GR4 team at No 41(R) TES remains busy in light of the type’s current heavy involvement in Operation Shader against so-called Islamic State. On March 2, its three remaining examples departed once again for Naval Air Weapons Station (NAWS) China Lake in California. The latest detachment will probably be the last for the squadron’s Tornados, however the unit’s Officer Commanding (OC), Wg Cdr Steve ‘Ras’ Berry, gives a wry smile as he says: “When I joined the unit in December 2014, the Tornado was going on its ‘last hurrah’ in spring 2015, then it was going to be in the autumn of 2015, but then we opted to leave the jets out there until spring 2016. We took them out again last autumn for High Rider 16-4 and now they’ve gone again. That’s the fifth ‘last hurrah’ the jet has had.” A few years ago it was decided to reduce the No 41(R) TES Tornado complement to two, but three had to be retained just to cope with the squadron’s workload. “The point is that she might be old, but she is so easy to get [new] capability on,” Wg Cdr Berry continues. “On the Typhoon and F-35 you really have to invest in technologies to get new stuff, but with Tornado you can just bolt it on. Which is why she is an absolute workhorse. She will keep going strong until the day she dies.” Update: Total now reached - Thank you!41 Squadron has now raised £456 for a replacement memorial plaque to go at the military cemetery at Scottow for the 6 servicemen who lost their lives in a coach accident at Sasbachwalden on the 21st May 1983. They were serving with 41(F) Squadron RAF on exchange with 421 Squadron RCAF. 5 of those lost were from a complete cross section of the Squadron: a SNCO Avionics, a Rigger, a FLM, MT driver and a safety equipper. The 6th serviceman was from II Sqn RIC at Laarbruch. Sgt Brian Roe J/T Michael Messenger SAC Paul Armstrong SAC Peter Fox SAC Derrick Swash SAC Stuart Winship Details of this year's memorial servicewww.spiritofcoltishall.com/

This year's memorial will be held at the Scottow Cemetery on the 18th May with serving personnel and Standards on parade. There will also be a dedication service of another new plaque from 41Sqn at the RAF Coltishall Memorial Garden after the service at Scottow. If you wish to attend please arrive at Scottow Cemetery by 10.45 for the service to begin at 11.00. Medals must be worn. This entry has been made possible by Willie Felger, who was on the Squadron during the changeover from the Bloodhound missile to the Phantom. 41(F) Squadron We knew from the beginning that Dink Lemon was destined to form a new squadron but nobody knew officially exactly what form it would take. Early in 1972 we heard that it was indeed to be No 41(F) Squadron under the command of Wg Cdr Brian “Dink” Lemon. In due course several crews, including Tony and me, we were released from our units and gathered in a brand new hangar (now occupied by the Battle of Britain Memorial Flight) to re-form this famous squadron. At the same time NCOs and airmen arrived from other units and assembled under the tender mercies of Warrant Officer Arthur Mulvana. The new hangar had empty rooms and offices with bare walls, basic furniture but no budget for decorations, so we had to set to and build our own. We scrounged timber and found the old copper top from the officers mess bar which had recently been replaced, and built our own crew room. We all mucked in and were well on the way to becoming a close-knit team. Similarly WO Mulvana set to knocking the ground crews into shape, starting with early morning parades. The story goes when first interviewed by the Boss – Mr Mulvana said the he knew nothing about Phantoms, but a lot about airmen, so if the boss would please look after the aircraft and the officers, he would sort out the troops – maybe one of his victims could elaborate. On the assumption that nobody would have willingly given up their best people WO Mulvana and the Engineering Officers did a superb job and the sqns reputation soon soared. The squadron’s role was currently held by a Bloodhound anti-aircraft missile squadron at West Raynham in Norfolk, and we were duly despatched for a hand-over ceremony to transfer the squadron Standard to our base at Coningsby. Having done it before I had the honour of being the Standard Bearer – a duty I carried out with respect, enthusiasm and, having been trained at Laarbruch by the RAF Regiment Queen’s Colour Squadron, no small amount of bullshit! With the Standard came boxes of memorabilia which were carefully secured in an empty room until much could be displayed around the squadron. The troops had a huge cross of St Omer fashioned out of railway sleepers and this was painted red and conspicuously fixed to the side of the hangar along with a large name plate. The squadron was famous for being in the thick of the Battle of Britain flying Spitfires out of Hornchurch in Essex. Many of its pilots were Polish and their hatred of the Luftwaffe showed in the results they achieved. Their wartime combat report originals were carefully kept in arch files by the Intelligence officer, who was Flt Lt the Lord Guisborough – apparently known as “Gizzy”! Some of the pilots had quite thick files whilst others, sadly, had only one or two entries. Forty-one was a unique squadron because it had two operational roles at the same time – and was declared to NATO as dual role in reconnaissance and ground attack. This was huge fun but tricky to do as it was quite demanding to stay current both by day and night.

But, we were a small team and we worked hard, led by an outstanding boss in Dink Lemon. He was calm and never lost his cool, but it was very plain when he was displeased and the culprit was made to feel ashamed that he had let the side down. It did not happen very often. He was a natural leader with a great sense of fun. Above all, he was utterly professional in his approach to the serious business of being the best. I remember one disgruntled OCU instructor muttering that he hated elites. “Yes, they are a real bastard” one of us replied – “particularly when you’re not part of it”! The squadron navigators became expert at using the Inertial Navigation and Attack System (INAS) which had been a rather inconvenient aid to basic navigation on our course. However, we now studied the beast and learned to use many of its facilities to good effect and became good at the black art of flying at low-level at night and in cloud – quite challenging and not inherently safe! Crew cooperation and trust in each other’s ability was paramount and it was a real act of faith by our pilots to fly accurately on instruments when we could sense high ground to the side and above us! Perhaps surprisingly, there was not a single accident. Night low-level – sometimes at very high speeds to test the ability of our recce sensors, particularly the Infra Red Line Scan, to cope - was exciting even over flat ground and I remember very clearly Tony and I flying up to 600 knots at 400 then 200 feet at night! A huge benefit was that we could display the INAS target on the Low Map facility of the radar and the 25 mile scale coincided well with a 1:250,000 topo map. Nevertheless, we navs still used a 1:50,000 OS Map for target runs. Route flying was done in multiples of 60 knots groundspeed so that timing was kept as simple as possible; 360 knots = 6 miles per minute, 420 = 7, 480 = 8 and so on but we were really guzzling fuel by then. A single He111, designated Raid 23A, entered into 13 Group from 12 Group just west of Dishforth at 15:29. The aircraft flew north over the town of Leeming and dropped bombs on RAF Leeming, slightly damaging some transports and wounding three people. The airfield’s anti-aircraft batteries engaged the aircraft with their 40mm gun, but the 13 Group Controller quickly vectored 41 Squadron to the area.

Four sections were in the air at the time, and the pilots converged on Leeming. At 15:35, Flt Lt Tony Lovell (X4683) sighted the He111 one mile northwest of RAF Leeming flying east at 1,800 feet at approximately 180 mph, and gave chase. At around the same time, Sqn Ldr Patrick Meagher and Sgt Plt Bill Palmer (X4718) also arrived in the area. Lovell made an attack on the aircraft, expending a single, four-second burst from dead astern, closing from 200 yards to 50 as he fired. This caused a small, unidentified piece of the aircraft to dislodge itself and fly off. However, he was unable to make a further attack as a result of “another Spitfire being close to [the] E/A”. After this, Lovell did not see the aircraft again. Palmer sighted the aircraft briefly between cloud patches and informed Meagher, who had not seen it. As such, Meagher told Palmer to follow it and take the lead. Meagher then glimpsed the aircraft, too, but when he turned to follow Palmer, got lost in cloud and took no further part in the pursuit. Palmer also momentarily lost the aircraft but soon spotted it again and quickly closed to within 100 yards to identify it. Palmer’s aircraft therefore appears to have been the Spitfire to which Lovell refers. Being in an advantageous position, and afraid he would lose the aircraft into cloud, Palmer attacked it immediately. Opening up from below and astern, he fired a three-second burst as he closed from 100 yards to just 20, resulting in heavy return fire from the Heinkel’s ventral gunner. Climbing above the bomber’s tail and out of his range, Palmer made a second attack from above and behind, once again closing from 100 yards to 20 as he fired a four-second burst, although this time with slight deflection. He saw no result of his fire, but also experienced no return fire from the dorsal gunner. It was later assumed this was the result of the gunner having been hit. He then dropped below and behind the aircraft again to make his third attack, on this occasion firing another four-second burst, from 40 yards closing to 20. The ventral gunner was likely hit during this attack as Palmer experienced no further return fire from him. His fire also caused the port engine to explode; pieces of the engine dislodged themselves and flew back towards him, and oil sprayed across his windscreen. When Palmer broke away, the Heinkel disappeared into cloud and was not seen again. He tried to locate it, and asked the Controller for a new vector, but his message was not heard. It was assumed this was the result of a number of sections being in the air at the same time and the Controller likely conversing with them when Palmer sought to contact him. Left little choice, he returned to base. The last pilot was on the ground at 16:25. Palmer submitted a Combat Report for the operation, in which it is recorded that he had expended 1,760 rounds in the attack. Lovell had fired 740 rounds, but despite his contribution to the Intelligence Report that was submitted for the operation, he did not make a formal claim for the aircraft and Palmer was therefore granted the whole victory: one damaged He111. It was his first claim. The aircraft claimed damaged today is believed to have been He111P-2, 5J+NL, WNr 1623, of 5/KG4, which crash-landed at Soesterberg in the Netherlands on return with 35% damage. The Flight Engineer/Gunner, Fw Wilhelm Rahrig, was wounded, but none of the other crew members were hurt. [Excerpt from "Blood, Sweat and Courage" (Fonthill, 2014). Sharing permitted, but no reproduction without prior permission, please] |

Photo Credit:

Rich Cooper/COAP Association BlogUpdates and news direct from the Committee Archives

August 2022

Categories

All

|