Association blog

|

6/10ths cloud with early mist and fog, in a southwesterly wind of 10 mph, and poor visibility. 41 Squadron was airborne on three patrols today, but was only called upon to intercept the first of the seven raids mounted by the Luftwaffe. Three of these were directed against Kent and London, two on Portsmouth, one on shipping in the Thames Estuary and one on Dover. Although the attacks were “more varied than hitherto”, they were generally of a smaller nature than recently. The first attack commenced when nine Me109s crossed in at Dover, penetrated as far as the Sittingbourne area, and dropped bombs in that area and at Dover. A second formation of nine Me109s crossed in 15 minutes behind them, and circled the Canterbury area until 08:30. 11 Group had Kenley’s 253 and 605 Squadrons in the air at the time, having been airborne since 07:35, and they were ordered onto the Maidstone patrol line in anticipation of the initial plots making landfall. When this occurred, 41 and 603 Squadrons were also sent up at 07:50, too, 41 Squadron’s contingent comprising ten pilots under Flt Lt Norman Ryder. The Wing was airborne minutes later and ordered onto the Rochford Patrol Line, but when the Kenley Wing intercepted the Luftwaffe, the Hornchurch Wing was moved onto the Maidstone line to replace them. 41 and 603 were subsequently ordered to intercept the second formation of nine, designated Raid 7, but did not see any sign of them. However, it was believed that the Luftwaffe had nonetheless seen them, as they were recognised by the Observer Corps to have turned about and dived for the French coast. The Kenley Wing was more successful, and although 253 Squadron was unable to engage the Luftwaffe, 605 Squadron succeeded in claiming one Me109 destroyed, two probable and four damaged, although they sustained the loss of their Officer Commanding, Sqn Ldr Archie McKellar, who was killed in action. It was on return from this patrol, however, that 41 Squadron’s Plt Off Norman Brown (P7507) had a flying accident that could have had a fatal outcome. He was amongst five pilots that inadvertently entered the London Balloon Barrage, and was lucky to have survived when he struck a balloon cable and crash-landed near Dagenham, just east of London. Brown was injured in the accident and his aircraft, initially considered to have only suffered Category C damage, was struck from charge ten days later. Brown recalled many years later that whilst the Squadron was on the patrol, the weather had deteriorated over Hornchurch during their time away, and B Flight’s pilots were directed to land at RAF Gravesend instead. This was executed without problem and they subsequently had sufficient time at the airfield to refuel and enjoy some breakfast before they were recalled to Hornchurch. However, as Flt Lt Tony Lovell’s aircraft would not start again, he was left behind at Gravesend and Plt Off Denys Mileham took the lead of the remaining five.4 As the weather was still poor, however, they flew in close formation but ultimately lost their way and accidentally entered the Barrage Balloon area east of London. In the low cloud cover, the pilots did not realise their error. They were below the level of the balloons themselves, and the cables would have been the only indication they were there. Under the prevailing conditions, however, the cables would have been practically invisible. Indeed, Brown saw nothing until he had struck one of the obscured hazards. He remembered, “The first I knew of any problem was the flight performing a very tight turn, at which point I struck a balloon cable. I thought of trying to get out but decided against it for a number of reasons. I slid down the cable, losing speed, finally stalling and doing a ‘flick roll’, at which point I lost a part of the wing and the cable apparently broke… and I went into a steep dive. In pulling out of the dive, I met serious control problems and the aircraft rolled onto its back and at this point I thought it was the end as I was only a few hundred feet up. Somehow or other the Spit was turned the right way up in a shallow dive and I found that as long as I did not try to pull out I could prevent it from turning again.” A Barking schoolboy by the name of Tommy Thomas was watching the incident from the forecourt of his grandfather’s garage on Ripple Road. He recalled seeing two Spitfires suddenly break through 10/10ths cloud just east of the old Barking Power Station, when the higher of the two suddenly banked to port with a balloon cable around the port wing. He remembered hearing a loud “swish and twang” as the cable hit the ground just in front of the petrol pumps. The balloon, to which the cable belonged, was located on the green opposite the Ship and Shovel Public House on Ripple Road. Still coming down at this time, Brown recalled that, “Luckily I spotted an open building site just beyond the railway line, so I directed the machine there. As the site was small and surrounded by houses, I deliberately aimed to strike a six foot metal boundary fence in the hope it would take some speed off. I recall automatically going to select ‘flaps down’ but the airspeed was much too high. On crashing, the aircraft turned over violently and the hood smashed closed and I was trapped for what seemed a lifetime and I suppose I went completely berserk, as I was sure I was about to be cremated.” After what seemed to Brown “an eternity”, he was rescued from his upturned aircraft and was able to walk away with no physical injuries. The incident would, however, continue to haunt him for many years to come. He recalled, “From that day I started a series of horrific nightmares and I could scarcely bear to sit in a Spitfire with the hood closed. […] In retrospect, and with the wisdom of years, it is clear that I should have reported sick or asked to be taken off flying temporarily, but no fighter pilot will ever willingly do either and certainly at twenty one I did not, and fought on, and turned down an opportunity to transfer to Training Command. Some days were hellish but on the whole I felt I was winning and continued to fly with the Squadron throughout Nov., Dec. [1940], Jan., and Feb.41.” Brown was extremely lucky to have survived the incident with no physical injury and was flying with the Squadron again that afternoon, prior to being released on two days’ leave. [Excerpt from “Blood, Sweat and Courage” (Fonthill, 2014); sharing permitted, but no reproduction without prior permission please. Image: © Robin Smith, “Seek and Destroy”, which has always reminded me of this event.]

0 Comments

The following was taken from this LINK You can vote for George Beurling to be the 'People's Spitfire Pilot' by following the link above and clicking on this article (5th one down). If successful, he will feature in the RAF Museum's 'Centenary' exhibition in 2018. George Beurling (1921-1948)Born in Montreal, Canada, in December 1921, George Beurling learned to fly at 17 and joined the RAF in September 1940. Beurling’s talent as a pilot, together with his excellent eyesight and outstanding marksmanship, were soon apparent. So, too, was a rebellious streak which would regularly get him into trouble with authority. From December 1941, Beurling flew Spitfire Vbs as a sergeant pilot with 403 Squadron Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), and then 41 Squadron. While with ‘41’ he angered his superiors by twice breaking formation to shoot down enemy fighters. Posted to fly Spitfire Vs with 249 Squadron on the besieged island of Malta, Beurling’s ‘lone-wolf’ tactics now paid off. Beurling returned to Britain, claiming two more victories with the RCAF, but his individualism and continued indiscipline led to him leaving the Service in October 1944. Overall, the maverick Spitfire pilot was credited with 31 enemy aircraft destroyed with another ten shared or damaged. Unable to adjust to civilian life after the adrenaline surges of combat, Beurling chose to fly for Israel in the first Arab-Israeli war. On 20 May 1948, aged 27, he was killed when the aircraft he was ferrying to the new state crashed on take-off at Rome airport.

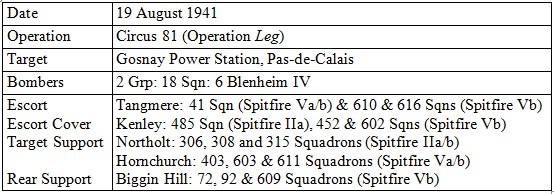

Originally posted on the website of the Bentley Priory Museum  When baling out of his stricken aircraft on 9 August 1941, Wg Cdr Douglas Bader was compelled to leave behind his right artificial leg as it was stuck in the cockpit. He unstrapped the prosthesis and jumped with only his left artificial leg, and was injured on landing, damaging the ‘good’ leg, and breaking the waist harness in the process; the leg that had remained... with the aircraft was destroyed when his Spitfire hit the ground. Bader was hospitalised for a short period in St. Omer, from where he managed to escape with the help of a French nurse, but had barely reached the home of a local farmer when he was found and re-captured. In much the same way that Galland, Mölders, and other German Aces were respected by the Allies, and indeed pilots before them such as von Richthofen and Udet, so too was Bader by the Luftwaffe. Being in a rather uncomfortable position without the full use of his legs, he therefore used his status to ask them if they might arrange for the RAF to drop a replacement right leg. In a rare case of collaboration between two countries at War, the Luftwaffe assented to Bader’s request and sent a message to the RAF to arrange it. Thus, Operation Leg was born, and formed a part of Circus 81 on the morning of 19 August. Officially, the aim of the mission was to attack Gosnay Power Station, which, ironically perhaps, was the failed target of Circus 68 on 9 August – the very operation Bader was lost on. However, the secondary, although preliminary, objective was to drop Bader’s leg by parachute. The Luftwaffe offered the RAF a safe thoroughfare to St. Omer but once the job was done the ‘ceasefire’ was over and the war was back on; the bombers and fighters would continue on to their attack on Gosnay. The Operation Order for Operation Leg foresaw the bombers making rendezvous over Manston at 10,000 feet at 08:30, with Tangmere’s Escort Wing stepped up and back at 11,000, 12,000, and 14,000 feet, the Escort Cover Wing at 15,000, 17,000 and 20,000, the Target Support Wings at 22,000, 24,000, 28,000, and 32,000 feet, and finally the Rear Support Wing at 28,000 and 32,000 feet. The orders pertaining to the dropping Bader’s leg also included a role for the Tangmere Wing: “The leg is to be dropped by a Blenheim when West of ST. OMER. The Wing Leader of the Tangmere Escort Wing is to report by R/T when the parachute has opened ‘LEG GONE’. Tangmere Controller is to report to Group Controller immediately he receives this message.” In the event, the Circus was delayed by two hours and the Tangmere Wing was airborne at 10:05, and rendezvoused with the Blenheims over Manston at 10:30. 41 Squadron deployed eleven pilots led by Sqn Ldr Gaunce and provided a Close Escort for the bombers at 11,000 feet. 41 Squadron comprised Gaunce P8759, Beardsley W3565, Rayner W3636, Mitchell W3383, Morgan R7350, Glen R7307, Marples W3713, Palmer W3564, Swanwick W3634, Bodkin R7304, and, Brew R7267. Kenley’s Escort Cover Wing also rendezvoused over Manston with the bombers and Tangmere Wing, and they proceeded together uneventfully to St. Omer via Dunkirk. At 10:57, 18 Squadron Blenheim IV, R3843, dropped Wg Cdr Bader’s replacement right artificial leg over the southwest corner of St. Omer Airfield from 10,000 feet; the parachute opened and Wg Cdr Woodhouse confirmed this fact to the Tangmere Controller. The specially built wooden crate that was dropped was clearly marked with a large Red Cross symbol, and landed near the village of Quiestède. The formation then continued on to Gosnay, approximately three-and-a-half miles southwest of Béthune, to complete the main objective of the Circus. Intent on making a bombing run at 10,000 feet, the bomber crews were once again foiled when they found ten-tenths cloud cover over the target area. This was mostly concentrated between 8,000 and 10,000 feet, but large cumulus clouds reached up to 20,000 feet, and storm clouds were scattered over the target area. This left them little choice but to abandon the attack, and Gosnay was spared yet again. No alternative target was located and no bombs were dropped at all. The Tangmere Wing did not sight the Luftwaffe all the way to the target, and turned with the bombers to escort them back out. The Blenheims’ return was initially covered by the same cloud cover that had thwarted their attack, but the weather deteriorated as they neared the coast and the bombers were forced to drop to just 1,000 feet to get under the cloud base. This resulted in them being fired at by the German coastal defences, which were no doubt surprised to see six RAF bombers roar over their heads at little more than 300 metres. The result was that all the aircraft were hit by Flak and one man was wounded. The Tangmere Wing sighted a few German aircraft on their way out but they showed no inclination to fight and were not engaged. The three squadrons left the bombers about ten miles off Manston and made for Westhampnett and Merston, where they landed in time for lunch at 12:00. The Kenley Wing, on the other hand, saw and engaged a number of Luftwaffe aircraft. 452 Squadron was attacked from behind approximately 15 miles inland and one aircraft was hit by cannon and forced to return home early. On the way back out, the Squadron was continuously attacked by Me109s, which split the pilots up, and cost the lives of Fg Off Eccleton and Sgt Plt Gazzard, whilst Plt Off Willis was wounded in action. In return, they claimed one Me109F destroyed and two probably destroyed. A section from 602 Squadron dived to attack three enemy aircraft below them without result, and another section was dived upon by three Me109s from above, but neither a claim nor a casualty was subsequently reported. On the way back out again, a number of small formations of Me109s also attacked 485 Squadron and several engagements took place, resulting in the loss of Sgt Plt Miller, for claims of one Me109 destroyed, one probably destroyed and one damaged. Northolt’s Target Support Wing made landfall on the French coast west of Gravelines at 10:45, stepped up and back at 22,000, 25,000 and 27,000 feet. Approximately five minutes after crossing in, they were attacked by 15 Me109s in two formations. 306 Squadron went into a defensive circle and subsequently claimed an Me109F destroyed for no loss, whilst 308 Squadron split up and claimed another destroyed, but lost the rest of the Wing in the process and patrolled the coast for ten minutes before returning home. 315 Squadron had difficulty maintaining contact with 306 and 308 Squadrons on account of cloud and were not engaged at all. However, pilots of the Wing report seeing an Me109 hit and destroyed by German Flak in the Calais area. Hornchurch’s Target Support Wing crossed the French coast six miles east of Dunkirk between 28,000 and 32,000 feet at 10:45. 611 Squadron sighted ten Me109s 24,000 feet over Poperinghe, Belgium, which they chased all the way to Dunkirk without result. 403 Squadron attacked another 15 Me109s in the Poperinghe area and ultimately claimed four destroyed, one probably destroyed and two damaged for the loss of Plt Off Anthony, who was shot down and captured, and Plt Off Dick who baled out off Dover with combat damage and was rescued by ASR. Soon after crossing in, 603 Squadron sighted 20 Me109s approaching from the south at 20,000 feet. They were engaged by one of the Squadron’s sections, which claimed two destroyed, two probably destroyed and one damaged for no loss, whilst the rest of the unit covered them at 30,000 feet. Ultimately, none of the Wing’s squadrons reached the Gosnay area, and they withdrew after they had been informed that the bombers had crossed out. Finally, Biggin Hill’s Rear Support Wing, made landfall on the French coast ten miles southeast of Dunkirk, between 27,000 and 28,000 feet. The Wing then made a wide sweep to starboard and in doing so sighted a number of formations of two to four Me109s at altitudes down to 13,000 feet. Whilst 72 and 92 Squadrons remained above for cover, 609 Squadron dived down to attack the enemy aircraft, and claimed two damaged. The Squadron’s Plt Off Ortmans sustained combat damage and baled out into the Channel but was picked up by ASR and returned safely. [Excerpts from my “Blood, Sweat and Courage” (Fonthill, 2014). Sharing permitted, but no reproduction without prior permission, please] Supermarine "Spitfire" Mk.I coded serial number N3126 EB-L of 41 Squadron of the Observer Corps, flown by Pilot Officer Ted "Shippy" Shipman, then based at RAF Catterick. On 15 August 1940 he shot down the Messerschmitt Bf-110C Zerstörer coded M8 + CH of Staffel 1 Zerstörergeschwader 76 -1./ZG76- piloted by Oblt. Hans Ulrich Kettling. The combat was filmed by the movie machine guns "Spitfire". The 3rd photo depicts what remains of Oblt. Hans Ulrich Kettling's Messerschmitt Bf-110C after the crash. The last picture shows Ted Shipman (left) and Hans Ulrich Kettling well after WW2, when they met in 1985.

Extract from One Of 'The Few". The Memoirs of Wing Commander TED 'SHIPPY' SHIPMAN AFC by John Shipman. To mark his 95th birthday, Warrant Officer (Retd.) Peter Hale RAF has taken to the air in a Spitfire again – the first time he has done so since 1945. On this occasion, he was a passenger in the Goodwood-based two-seater SM520. Arranged by author and Westhampnett historian Mark Hillier, the flight was provided courtesy of his colleagues at the Boultbee Flying Academy. The Academy offers flights and experiences around the UK in an ever-expanding fleet of owned and managed Second World War aircraft, including SM250. Completed in the Castle Bromwich factory on 23 November 1944, SM250, initially built as a single seat Mark H.F.IXe high level fighter, was delivered to No.33 Maintenance Unit at Lyneham in Wiltshire where it was to be prepared to operational standard for service delivery. Fitted with a Rolls-Royce Merlin 70 V12 engine, SM 250 was sold to the South African Air Force on 21 June 1948. One of a batch of 136 Spitfires earmarked for delivery to South Africa between 1947 and 1949, it is known that SM250 was off-loaded at Durban in 1948. Eventually sold as surplus, SM250 was registered in the UK in 1997, following which the decision was taken to convert her into a Trainer 9 two-seater. With Jez Attridge, the former Officer Commanding RAF Coningsby at the controls of SM250, the flight was an emotional experience for Peter – stirring memories of his time flying Spitfires with 41 Squadron between August 1944 and August 1945. One sortie that he recalled was a 125-Wing operation from Celle, Germany, on 24 April 1945. Peter recalled how on this day the Wing, led by Group Captain Johnnie Johnson, headed east towards Berlin following reports of a large concentration of airborne German aircraft. It was discovered, however, that they were in fact Russian ’planes attacking retreating German troops around twenty-five miles WNW of Berlin. Peter, then a 22-year-old NCO pilot, noted how the Red Air Force fighters ‘were all over the sky with no obvious formation. They suddenly appeared in the sky like a swarm of bees.’ The RAF pilots, however, proceeded to join the Russians in their ground attacks, this being one of the few instances of contact between RAF and Russian fighters during the war. Having joined the RAF in January 1941, Peter undertook his elementary flying training in the UK before being shipped to Canada to undertake his service flying training. However, rather than being sent home for operational duties after receiving his Wings in April 1942, he was retained in Canada for a further eighteen months as a staff pilot and instructor. Finally released in October 1943, he returned home from New York on the majestic troopship Queen Mary. After advanced flying and operational training, he was posted to 41 Squadron on 8 August 1944, by which time he had been promoted to Warrant Officer. From this point on Peter was in the thick of the action, commencing with patrols over south-east England to combat the flying bomb threat. These sorties were closely followed by others that were part of the hunt for V2 and V3 sites, escorts to USAAF bombers involved in the Oil Campaign, and air support for Operation Market Garden.

In December 1944, 41 Squadron moved to the Continent. It spent the ensuing months venturing deeper into Germany, mainly deployed on attacking ground targets behind the front. Its Spitfires were also regularly involved in brief but aggressive aerial combats. When, in mid-April 1945, 41 Squadron moved to Celle Aerodrome, approximately 140 miles west of Berlin, it became one of the first Allied air units to be based east of the Weser. Following the German surrender, Peter remained with 41 Squadron until August 1945, when he was posted out to India. Returning home in time for Christmas 1945, he was demobilised in June 1946. Peter spent the next thirty-five years with the Met Office, but did not fly a Spitfire again until the flight in SM520. “There was an almighty bang and everything changed. After the roar and racket of the past quarter of an hour, there was suddenly total silence. There was glass everywhere except in the instrument panel where it belonged. My right arm wouldn’t obey my commands but hung loose at my side. Almost every dial, indicator and gauge in front of me had gone haywire. Not a squeak from the radio; not a murmur from the engine; no wind noise; total silence; and around me total chaos.” Sgt Plt Peter Graham, 41 Sqn, on being hit by Flak, when a 20mm high explosive shell entered his cockpit, during a Rhubarb* to the Le Havre area, 23 July 1943. As quoted in "Blood, Sweat and Valour" (Fonthill, 2012), and reproduced with Peter's permission. * Term used to describe raids over over France – either ‘sweeps’ involving the whole squadron, or ‘rhubarbs’ when a pair of aircraft would go out on a roving patrol.

Instigated as part of a campaign to seize air superiority from the Germans in preparation to a landing in Europe 4 July 1944 – Poor weather continued throughout the morning, with cloud and mist. The first wave of V1s did not come over until 08:30, but thereafter 108 were plotted by 11 Group. Of these, 84 crossed the coast and 52 were shot down by fighters.

Weather conditions prevented 41 Squadron from getting airborne until after lunch, but from 12:40 onwards twelve anti-Diver patrols were flown over the Channel, southeast of the Isle of Wight, and the last pair landed at Friston at 22:30. However, despite their efforts, just one victory could be claimed by the Squadron, which was shared between Fg Off ‘Momo’ Balasse and Flt Sgt Freddie Woollard on the third patrol. Blue Section (Balasse EN229 & Woollard MB856) was airborne at 14:10 to patrol an area ten miles out to sea between Hastings and Rye. The pair were vectored onto a Diver by Wartling Control at 14:30, and soon spotted it approaching Dungeness at 3,000 feet on a course of 340° and at an IAS of 340-350 mph. Balasse and Woollard took turns firing on the V1, attacking it from quarter astern to full astern, at ranges of 250-200 yards, and sent it down to explode on impact at a location they described as “approx. 1 Mile W. of Lydd. (actually N. of Rye.)”. They returned to base at 15:30, claiming the Squadron’s fifteenth destroyed V1 (13 + 2 shared). [Excerpt from "Blood, Sweat and Valour" (Fonthill, 2012)] This article was originally posted on the RAF Website. RAF Coningsby Gate Guardian, Phantom FGR2, XT891

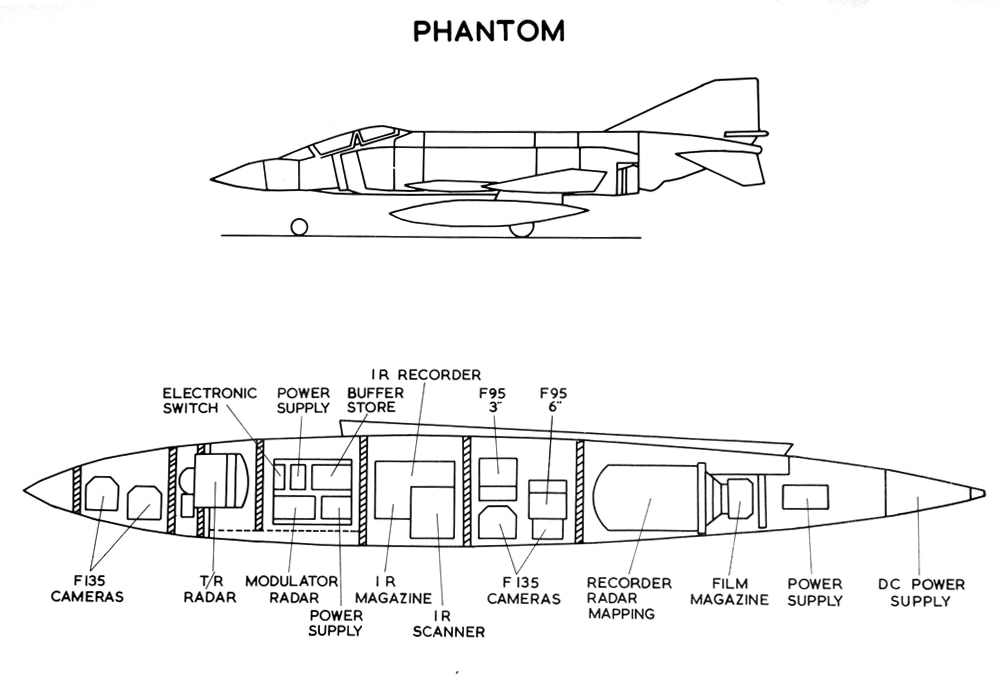

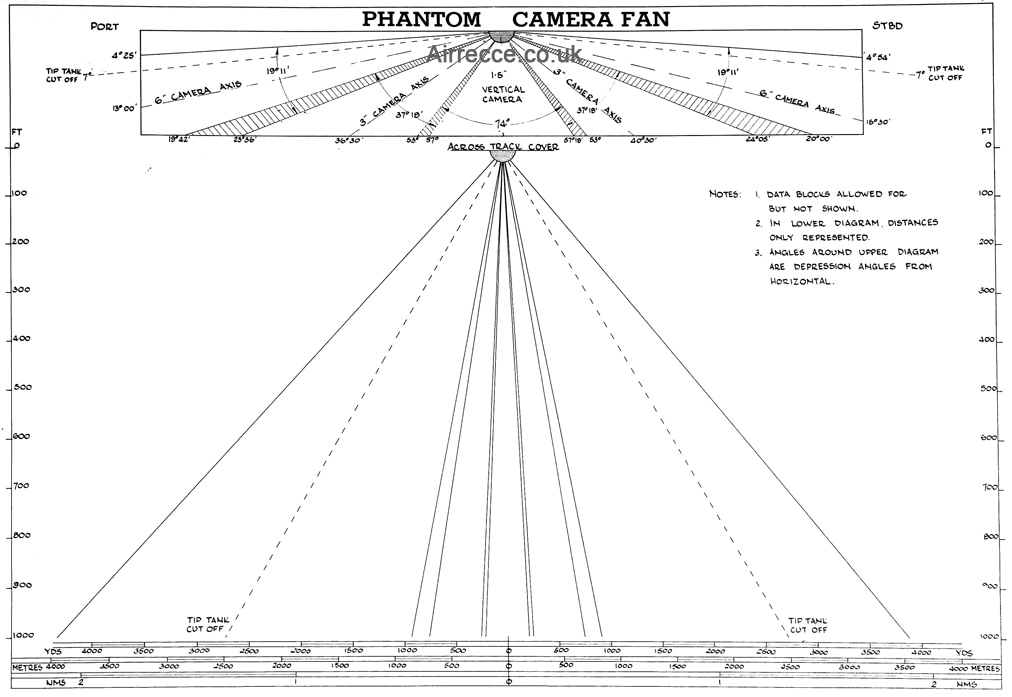

Some aircraft hold a special place in RAF history and XT891, the RAF Coningsby Gate Guardian is certainly one. It was not the first Phantom delivered to the UK as that accolade goes to a prototype YF-4K which first flew on 27 June 1966 at the McDonnell Douglas plant in St. Louis. XT891, however, was the first delivered for operational service to the Royal Air Force. Group Captain Stanley Mason formally accepted XT891, an F4M designated the FGR2 (Fighter, Ground Attack, Reconnaissance) in RAF service, in a ceremony at RAF Aldergrove on 20th July 1968. After acceptance, it arrived on 228 Operational Conversion Unit, or OCU, on 23 August 1968. A twin stick variant, the rear cockpit had a different configuration to the normal Phantom. The layout of the cockpit consoles was revised to accommodate the throttles which were mounted on the left. Although these operated normally in the military power range, reheat could not be selected in the back. An enhanced flight instrument cluster sat at eye level in the back seat, although it restricted the forward view considerably. The floor mounted control column allowed the flying instructor in the rear cockpit to take control when needed. The “stick” could be removed to allow the radar scope to be pulled out from its housing, otherwise impossible if a stick was installed. For intercept training sorties this was the preferred configuration, although occasionally it remained fitted, allowing the staff navigators some “stick time”. The trainer configuration was less common and each operational squadron had only one twin sticker although a much higher proportion were operated by the OCU at Coningsby because of the increased training task as pilots converted to the Phantom. In all other respects it was fully capable operationally. Soon after its arrival XT891 moved across to 54 Squadron in the ground attack role remaining at Coningsby for some years serving another short stint on the OCU. When 56 Squadron reformed with Phantoms it became the Squadron “two sticker” serving as “Zulu” at RAF Wattisham before returning to the OCU at Coningsby and, eventually moving to RAF Leuchars where it wore the tail letters “Charlie Zulu”. Another stint at RAF Wattisham as “Sierra” on 74 Squadron ended its service career and it returned to its spiritual home at RAF Coningsby. Once retired, officially, it adopted a ground instructional airframe number, 9136M, although it continues to wear its operational registration marks. Soon after being placed on display as the Station Gate Guardian it was repainted in the colours in which it first served in 1968. The square fin cap for the radar warning receiver was removed to return it to its original configuration and it reverted to the grey and green camouflaged pattern with red, white and blue roundels reminiscent of its early service during the Cold War. In subsequent years both 6 Squadron and 41 Squadron, both of which operated the type but not the actual airframe, laid claim to the airframe adding their own squadron markings. The following information has been collated from: www.spyflight.co.uk/ and www.airrecce.co.uk/ together with assistance from Ray Dunn. In 1964 the Labour government of Harold Wilson cancelled the P1154 and TSR-2 programmes, leaving the RAF without obvious replacements for the Hunter and Canberra in the fighter, ground attack and reconnaissance roles. The RAF eventually decided to follow the Royal Navy's decision to purchase the McDonnell Douglas F-4 and in Feb 65 placed an order for 118 F-4's to take over the roles of the Hunter and Canberra. In RAF service the Phantom was known as the FGR2, with the initials standing for Fighter, Ground Attack and Reconnaissance. Unlike the USAF and US Marines, the RAF did not obtain Phantoms that was solely for photographic reconnaissance, the RF-4 series. The F-4 OCU at Coningsby was formed in Aug 1968 and the initial output of graduates formed the ground attack squadrons in Germany and UK. The first dedicated F-4 reconnaissance squadron to form was 2 Sqn based at Laarbruch in Germany which stood up in Dec 70. This was followed by 41 Sqn at Coningsby which formed in Apr 72. Only some thirty F-4's were specially wired to carry the EMI reconnaissance pod and these aircraft equipped 2 and 41 squadrons. The pod was pressurised and mounted on the aircrafts centre-line position, looking like a 500 gal external fuel tank, it had a fat bottom and an air scoop on each side of the pods forward nose section. Using a considerable amount of technology originally developed for the TSR2 reconnaissance systems, EMI eventually created the biggest, most capable and most expensive reconnaissance pod of the 1960s.  Starting at the front the pod was fitted with the following equipment, two AGI F.135 cameras, a Texas Instrument RS700 infar-red linescan (ILRS) sensor, four F.95 cameras in the oblique position, these could replaced with another split pair of F.135 cameras for night tasking. All of the F-135's were vertical facing. When in the 'Night-Flashing' mode, four F-135's were used, three of them were arranged in a split-pair 'fan', the fourth camera was used as a timer unit to synchronise with the electronic flash unit in the port Sargent Fletcher tank. Along each side of the pod were the 15 ft slotted waveguide aerials for the MEL/EMI Q-band Sideways Looking Reconnaissance Radar (SLRR). This scope of reconnaissance equipment fitted gave a horizon-to-horizon coverage, however, there was a loss of 4½° on each horizon due to the external fuel tanks mounted under the aircrafts wings. For special tasks, a F126 vertical camera and an F95 oblique camera with a 12in focal lens could also be fitted. The only 'forward-facing' camera used was an F-95 in the 'Strike-pod' which was fitted to the port forward sparrow position. It had a depression angle of 20° from the horizontal.  The exposure rate of each camera could be selected to run at 4, 6, 8, or 12 frames per second, though normal settings were either 8 or 12 depending on what height the aircraft was flying. The IRLS could cover an area of three times the aircrafts height. When using the SLLR the aircraft had to fly straight and level as the system was not roll stabilised. The system could cover an area of five miles when the aircraft was operating at normal low-level height, this increased to ten miles when flying at 6,000ft, however, there was a degradation of image quality. The Jaguar used a new build EMI recce pod when it took over the role of tactical reconnaissance from the FGR2 in 1976. The Jaguar pod featured a different mark of F-95 camera (Mark 10), and used a different IRLS, 70mm rather than the 5'' format used on the Phantom EMI Pod. |

Photo Credit:

Rich Cooper/COAP Association BlogUpdates and news direct from the Committee Archives

August 2022

Categories

All

|

||||||